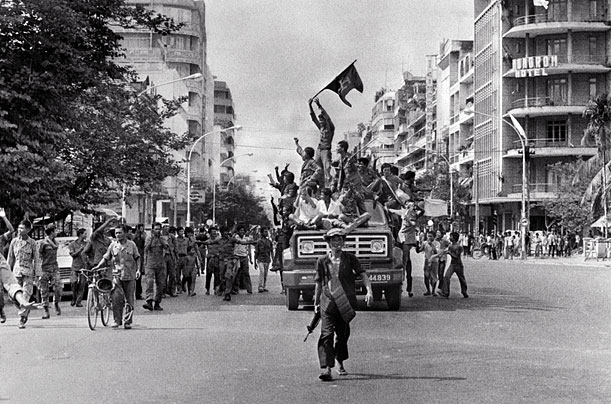

Angkar was the shadowy, omnipotent entity controlling Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge regime (1975-1979) under the rule of Democratic Kampuchea. Although its name translates simply as “the organization,” Angkar was much more than a bureaucratic body. It was the mysterious and authoritarian force behind every decision made during the reign of the Khmer Rouge.

To the Cambodian people, Angkar was faceless, omniscient, and omnipotent. The reality, however, was that Angkar was the operational arm of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), dominated by a small and secretive group of individuals who made all major decisions.

The Meaning of Angkar

Angkar, meaning “The Organization,” was both the heart of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and its operational face. During the rule of Democratic Kampuchea, Angkar replaced any notion of individual leadership, embodying the idea of a faceless, collective authority. It was this mysterious identity that instilled fear and reverence among the population. People obeyed Angkar, knowing that it could reward or destroy their lives, without ever knowing who was behind it.

Angkar was more than just a euphemism for the state; it was a complete organizational structure through which the regime’s policies—ranging from agrarian collectivization to forced labor and mass purges—were executed. While Democratic Kampuchea had nominal institutions, such as the State Presidium and the People’s Representative Assembly, the actual decisions came from the Standing Committee of the CPK, the small group of leaders who wielded absolute power.

Relationship Between Angkar and the CPK

At its core, Angkar was synonymous with the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). The CPK held total control over the governance of Democratic Kampuchea, rendering any other formal political bodies meaningless. The Standing Committee of the CPK, a small group of high-ranking officials, made all significant decisions, from the forced evacuation of cities to the collectivization of agriculture. Although Angkar presented itself as a unified, faceless entity, the power rested in the hands of a few elite leaders who governed Cambodia with an iron grip.

The decisions of the CPK and its Standing Committee were implemented by lower-ranking cadres and enforced by the Brother system, a hierarchy of leadership that extended across every level of Khmer Rouge authority.

The Standing Committee of the CPK

The Standing Committee was the nucleus of power within the Communist Party of Kampuchea. This small group of key leaders shaped every aspect of Democratic Kampuchea’s governance. The Standing Committee’s membership hardly changed throughout the Khmer Rouge’s time in power, underscoring the group’s tight control over the regime.

Here are the key members of the Standing Committee during the Democratic Kampuchea period:

- Pol Pot (Saloth Sar) – General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea

Pol Pot was the undisputed leader of the Khmer Rouge and the primary architect of Democratic Kampuchea’s radical policies. - Nuon Chea – Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea

Known as Pol Pot’s closest confidant, Nuon Chea played a central role in both the ideological direction and day-to-day governance of the regime. - Ieng Sary – Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs

Ieng Sary managed the regime’s foreign relations, especially with China, while also helping to oversee the diplomatic isolation of Democratic Kampuchea from most of the international community. - Son Sen – Minister of Defense

Son Sen was in charge of military operations and internal security, playing a critical role in the purges and ensuring the regime’s grip on power. - Khieu Samphan – President of the State Presidium

As head of state, Khieu Samphan was the official face of Democratic Kampuchea, though his role was largely symbolic in comparison to the true decision-makers within the Standing Committee. - Ta Mok (Chhit Choeun) – Military Commander

Known as “The Butcher,” Ta Mok controlled large swathes of territory and was feared for his ruthlessness, particularly during purges. - Vorn Vet – Deputy Prime Minister in charge of economic planning

Vorn Vet played a leading role in Democratic Kampuchea’s agricultural policies and was deeply involved in the regime’s efforts to collectivize the economy. - Ke Pauk – Senior Leader

Ke Pauk oversaw the Northern Zone and played an instrumental role in executing Khmer Rouge policies in the countryside.

The “Brother” System of the Khmer Rouge

One of the defining characteristics of the Khmer Rouge leadership was the “Brother” system, a hierarchical structure where top leaders referred to each other by coded “Brother” numbers rather than names. This system maintained a sense of secrecy and reinforced unity among the leadership, making it difficult for both insiders and outsiders to discern who was in control of specific policies or regions.

While Pol Pot was commonly known as Brother Number One, other key leaders had their own designations within this system:

- Brother Number One: Pol Pot (Saloth Sar) – The supreme leader of the Khmer Rouge and mastermind of Democratic Kampuchea.

- Brother Number Two: Nuon Chea – Pol Pot’s deputy and chief ideologue, instrumental in shaping the regime’s revolutionary policies.

- Brother Number Three: Ieng Sary – In charge of foreign relations and key diplomatic figure.

- Brother Number Four: Son Sen – Head of defense and responsible for internal purges.

- Brother Number Five: Khieu Samphan – The regime’s nominal head of state.

- Brother Number Six: Ta Mok – Military commander responsible for brutal purges, particularly in the Southwest Zone.

- Brother Number Seven: Ieng Thirith – Minister of Social Action and one of the few women in the upper ranks of the regime.

- Brother Number Eight: Ke Pauk – Senior leader overseeing the Northern Zone.

- Brother Number 13: Ros Nhim – Responsible for the Northwest Zone, later purged by the regime.

- Brother Number 15: Koy Thuon – A senior official overseeing the Northeast Zone, also purged during internal power struggles.

- Brother Number 89: Meas Muth – A senior naval commander in charge of maritime operations and military purges.

These numbers not only indicated rank but also served to maintain secrecy among the Khmer Rouge leadership. The identities behind these “Brothers” were often unknown to the general public, helping to maintain the image of Angkar as an impersonal and all-powerful organization.

Angkar’s Role in Democratic Kampuchea

During the rule of Democratic Kampuchea, Angkar controlled every aspect of Cambodian life. The policies of forced collectivization, mass evacuations of urban populations to rural labor camps, and the total eradication of private property were all directed by Angkar. The organization also implemented a rigid social hierarchy, with soldiers and loyal cadres receiving preferential treatment, while intellectuals, minorities, and “enemies of the state” were systematically eliminated.

Angkar’s rule was enforced through a vast network of security agencies and local cadres, who monitored the population for any signs of dissent. The regime’s policies led to widespread famine, forced labor, and mass executions, as Angkar sought to create a self-sufficient agrarian society based on the radical principles of the CPK.

Purges and Consolidation of Power

One of the most brutal aspects of Angkar’s governance was its constant purging of perceived enemies. Even senior Khmer Rouge officials were not immune. Figures like Ros Nhim (Brother Number 13) and Koy Thuon (Brother Number 15) were executed as Angkar sought to consolidate its power. The purges extended to ordinary Cambodians as well, with the notorious S-21 prison in Phnom Penh becoming a symbol of the regime’s brutality. Those detained at S-21 were often accused of being traitors or spies and were systematically tortured and executed under Angkar’s orders.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Angkar

Angkar was much more than a faceless organization. It was the operational force behind the Khmer Rouge’s radical experiment to reshape Cambodia into an agrarian communist utopia. The leadership of Angkar, dominated by the Standing Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), remained largely unchanged throughout the regime’s existence, maintaining tight control over all aspects of life in Democratic Kampuchea.

The Brother system within the Khmer Rouge leadership not only served to solidify the hierarchy but also obscured individual responsibility for the atrocities committed during this period. Angkar’s policies, driven by secrecy, paranoia, and radicalism, ultimately led to the deaths of nearly two million Cambodians through starvation, forced labor, and execution.

Even after the fall of Democratic Kampuchea in 1979, the legacy of Angkar and its brutal rule continues to haunt Cambodia, serving as a dark reminder of the dangers of totalitarianism and unchecked power.